This is exactly what happens in dance. We do a whole dance, but the only comment we get is, your hands are floppy. Someone else says, your shoulders are tight. Some else disses your hair. And so forth. So we end up constantly scanning for these hot button corrections–which makes us feel anxious and hunted.

This affects us when we look at our own dance, too. Do you cringe when watching your own videos? I did. All I saw were my mistakes, and they consumed me with shame. I never even noticed what I did well. What about the dance? The content, the ideas? Use of the stage? Music choice and representation? Why do we so often focus on these red-herring technical corrections instead of substantive elements like structure and content?

The sad truth is, most folks don’t know how to give productive critique. They only tell us what not to do. They notice some annoying technical detail–and that’s all they focus on. Or they have an ulterior motive to be better than us, so they cut us down with mean comments. We feel bad about ourselves and our dance. What good does this do? None. How does it help? It doesn’t.

How can we do better? Ah, now we’re talking.

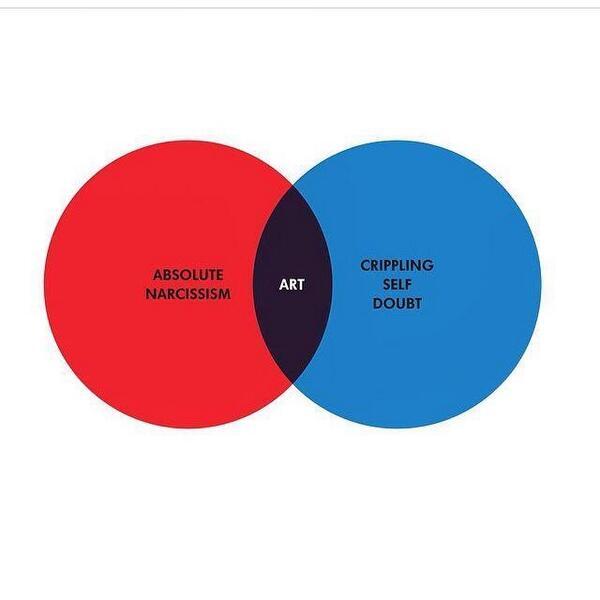

Productive critique is a collaboration. As respondents, we look at the big picture, understand the artist’s vision, and empower them to find their own way.

Productive critique helps us make better art. All artists need feedback. We don’t have the expertise and perspective to see where we cut a corner, missed a mark, or lost an opportunity. An outside eye can see more clearly than we can. But that outside eye needs to know what to look for. Productive critique empowers us to see our own art–and everyone else’s–with fresh, compassionate eyes.

See the Big Picture.

Higher Order Concerns (HOCs) are the top level of our art. Is the dancer enjoying herself? Does she share her joy with the guests? Is she one with the music? These are the trifecta of mastery in Oriental dance. Focus on these elements first. Everyone loves a relaxed, happy dancer whose joy includes the guests as she embodies the music, right? If these are yes, celebrate! Then you can go deeper. If the answer to any one of these is NO, the critique stops. Everything takes a back seat to this.

Sure, we all have technical issues. Yes, they are important. But these are Lower-Order Concerns (LOCs). That typo is a superficial thing, easily cured by proofreading When people don’t know how to assess structure and content, they become fixated on small tech issues. As a writing teacher, I have learned to look past technical errors to see the big picture–and I have learned to do this in dance as well. So can you. And it’s worth the investment.

When we focus on HOCs, many tech glitches disappear–all by themselves. How does this happen? When we feel confident, we dance better. When we have something to say, we want to say it well. We start to notice things all by ourselves and address them. It’s a big win-win.

Understand the artist’s vision.

As artists, we have a specific ideas we want to convey. If a respondent isn’t on the same page, they may steer us in a direction far removed from where we want to go. For this reason, it is more productive to ask questions than to give opinions–especially unsolicited opinions.

Once we know where the artist wants to go, we can help them figure out how to get there. This includes observing and highlighting what they are doing right. People need to now what to do more of. Plenty of people will tell you what you are doing wring (in their opinion). It takes a keen eye to notice what is good and to celebrate that.

PS If the artist doesn’t ask, don’t dump your vision on their head. If you have an observation or opinion about a dancer’s work, ask first if they would care to hear it. And remember, no means no. Artist’s have to find their own way. A lot of “errors” can be chalked up to youthful inexperience. Shaming a dancer for her choices is pointless and destructive.

Empower the artist to find their own way.

Nobody likes to be told what to do. But we do love to discover. When a thoughtful discussion helps us to see where we want to go and understand the various ways to get there, we can make informed choices about how best to proceed. If the obvious trail is rife with bandits and steep cliffs, it’s nice to know that. But it is our choice to proceed.

What about Self-Critique?

Many of us have no tools and no reliable respondents. We can use these same tools to help ourselves move forward. The other most important thing is The first step is separating ourselves from the dancer (and the dance), in the video. She is not us! She is Video Girl. From there, we can assess Video Girl based on HOCs instead of LOCs to see what she is doing right, and where we can help her improve.

If a writer doesn’t know what point they want to make, nothing else is going to work. But if the editor can’t get the point because all they see is a typo, nothing’s going to work either. It’s the same in dance. Find your dance’s point, and point everything in that direction. Relax! Have fun, enjoy the music, and share your joy. Your dance will instantly improve, and so will the rest of your life.

Love,

Alia

For more on Productive Critique, check out the course

Focus on the Feeling: How to Get and Give Great Critique

https://aliathabit.com/dancers/focus-on-the-feeling/

No comment yet, add your voice below!